A Practical Definition of Scenography

The term “scenography” still flusters much of the Anglophone world, where it suffers the reputation of being new-fangled, pretentious, anti-textual or all three. My purpose here is to demonstrate that it is at least neither new-fangled nor pretentious. Its textual implications are too complicated for this essay, but one can at least show that insisting on a text / image dichotomy does not constitute a fair definition of scenography.

Were we not to confuse scenography, the practice, with a style of scenography espoused by modernists like Josef Svoboda, we might be as comfortable with the term as are working-class Europeans or South Americans for whom it is a household word.

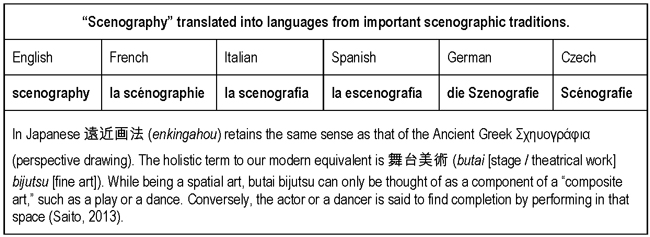

Kaelin, Valérie C. A Scenography Glossary. 2013.

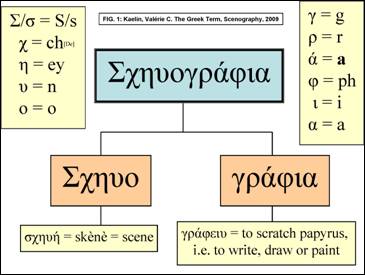

First, scenography is not, as some believe, a term invented by the Central Europeans during the Cold War with which to flaunt their aesthetic experimentation. Granted, its meaning has changed to keep pace with emerging practices. In The Origin of the Bicameral Mind, Julian Jaynes’ lyrical passage on the etymology of words shows us how, in realspace the leaf falling from a tree, given technological innovation, may metaphorically become the leaf of a hard copy book (49-50), (the pages of which might even be made of wood pulp!) As regards the practice of scenography, Jacques Polieri (Scénographie Semiographie, 1971) traces the evolution of the word from an Ancient Greek scenic - see how it is impossible to avoid the root word - practice of painting a setting on panels in front of a shed, the skènè, where actors and props were concealed from the audience as needed to maintain the integrity of a performance (1971, 8). Here is a diagram of our term’s etymology:

Kaelin, Valérie C. The Greek Term, Scenography, 2009 |

Polieri reminds us that Aristotles’ Poetics IV, 1449 and the second chapter of Vitruvius’ De Architectura, (c. 57 BC) both mention “scenography” along with other methods of scenic representation (7). Greco-Roman texts, as we know, were preserved in the Middle East until they were later re-introduced to Europe by the intellectuals of the Italian Renaissance under the patronage of merchant-

statesmen. The names of forms of representation demonstrated in them, including that of scenography, are taken up again in Marolois’s Traité de perspective (La Haye, 1614), whom Polieri quotes at length (9). |

The Renaissance perfected perspective painting for site specific images and works of art on panels or canvas, while their theatricals were still actually immersive, often taking place in appropriated private or public spaces. The conceit of a perspective painting come alive had its heyday in the 17th and 18th century with the wing and drop theatre. The innovations of De Loutherbourg in the late 18th century, says Winslow (2008), began a trend toward more interactive scenery by introducing piercings and hidden ramps as well as silk filters in order to colour light (14). The proscenium theatre of the 19th century, while still using scenic painting, became increasingly realist—read: real-spatial—in its depiction of settings. Electricity, from its last quarter, and then digital technology, in the 20th, revolutionized and diversified opportunities for scenographic invention: Beyond the theatrical machine called the proscenium stage, scenographic experimentation evolved to include:

(a) architectonic performance spaces awash in light,

(b) motion pictures and,

(c) a return to the street theatre of the Middle Ages (assisted with projections and neo- baroque machines) by the new media.

This is how the leaves of our theatrical canopy scattered like sequins.

Having established that the term “scenography” is not new, let us examine its serviceability: The diversity of venues for the art of scenography does not preclude a coherent practice. These include:

(a) To establish and populate a designated space for the deployment of a performance:

(b) That performance implies a dramatic narrative requiring interpretation and enhancement by cohesively extending its values in a tangible manner.

(c) All is lost if the scenographer cannot think choreographically, because the responsibility is to design a course for every anticipated movement within the designated space (Payne, 1981; Kaelin and Homayouni, 2012).

(d) The working process is highly collective, with a tradition of presentation and communication skills that assure the smooth operation of its interdisciplinary projects.

In film, “scenography” is sometimes referred to as “art direction.” This seems inadequate, since an “art director” could just as easily be in charge of the layout of a magazine ad campaign. Certainly, that job also requires interpretive skills to provide the editorial concept its cohesive physical appearance. However, it is not a spatial art. Therefore, calling a scenographer an art director is at best a confusing, and therefore weak, form of advertising one’s services. “Production designer” comes closer, perhaps, but one wants to ask, the production of what? To say that one is a scenographer is the easiest way to claim a specialty in providing the material culture for a performance. Whether a film, an opera, or an installation, one has inherited a practice at once literary, sculptural, choreographic and collaborative. No one can be confused by the specificity of the term scenography, hence, it is serviceable. And, if it is the most serviceable definition, then it can not be pretentious.

Because of the scope of motion picture production, the addition of the moving camera, as well as the impact of Hollywood production practices, film scenography is normally managed in silos. The stamina required to manage either production design / art direction, costume design, or lighting is already herculean. It is difficult to imagine the special circumstances that would inspire the producer and department heads to work with its scenographer using a theatrical hierarchy. Ostensibly, the art department’s production designer provides a film’s unifying scenographic vision.

Theatre scenographers are more multidisciplinary. Whether insisting on a signature vision, or merely budget-strapped, the artistic director might make the designated scenographer responsible for the sets, costumes and lighting, although it is more common for the scenographer to produce sets and costumes [(hiring an additional lighting designer)] or sets and lighting [(hiring an additional costume designer)]. For dance theatre, the scenographic image may be driven by costumes and lighting only. Each scenographer is free to develop multiple expertises; each production to bundle the practice as suited to its needs.

According to Associated Designers of Canada, categories of scenography include:

Set Design

Costume Design

Lighting Design (including Projections)

Sound Design (added in 2005)

These scenographers might perform any or several of these job titles for one or another production. Also, the same scenographers might practise their craft in a variety of media: live theatre, motion pictures, installations, or exhibition curation. The ability to apply scenographic problem-solving to a range of venues strengthens the practitioner’s employment options. It might only mean, in Canada, the necessity of being represented under different union jurisdictions organizing their respective media. US scenographers are fortunate in being inclusively represented under United Scenic Artists 829 as “artists and designers working in film, theatre, opera, ballet, television, industrial shows, commercials and exhibitions” (Home Page; “Introduction;” ¶ 1). One cannot omit that television’s “lighting director” / film’s “director of photography” is organized as a cinematographer under the camera union locals in North America.

Confusing the practice of scenography with a style of an artist or a single tradition is best refuted by accessible analogies with other arts. Here are some:

(a) Do we conflate the choreographic style of Martha Graham with the entire tradition of modern dance? (The Svoboda = scenography fallacy.)

(b) Whether Charles Frederick Worth, the 19th century European, or Rei Kawakubo, a 20th century Japanese, are we confused by their statuses as fashion designers? (Scenography crosses historical periods and geographic locations.)

(c) Are not Steve Jobs and Henry Ford both entrepreneurs? (Scenography bridges a variety of technologies and ventures.)

Similarly, the prejudice that scenography is anti-textual may be laid to rest, since providing the material culture for a performance is a necessity regardless of its textual considerations. Scenography, through its use of meaningful ciphers to extend the values of the text, provides a complementary textuality, in the same way that we understand the immersive environment of Chartres Cathedral to be at once the extension of the Catholic mass and of Celtic traditions that preceded it on the same site. It is when its complementary function appears to compete with the performance or misrepresents the text’s intention that it seems hubristic. Still, that is not the fault of the nature of scenography itself. The responsibility of generating the textual purpose and of marshalling the performance style lies elsewhere. We should keep in mind too that the performance is still textual, even if without dialogue, as in the physical theatre or in silent films. Whether designing for Tim Robbins’ Dead Man Walking or for Le Cirque du Soleil, the scenographic team is still busy at its trade.

To use a final analogy, one can see an apt comparison to the individual who states that they practise medicine. In conversation, we might ask: “what branch?” “which area of expertise? or “which specialty?” The doctor of medicine, whether general practitioner, neurologist, surgeon, or otolaryngologist; in private practice, a community clinic or a research hospital, is still practicing the fine art of healing. The same permutations apply to the person who declares: “I prastice scenography.” Their practice is clearly contextualised. Their specialty, the venues in which they tend to work, their aesthetic sensibilities or the sorts of projects they prefer all emanate from that definition. We may also surmise that the evolution of an art, from ear-candling to otolaryngology, or cave painting to projected scenery, share a techno-cultural trajectory.

I hope to have crafted here an accessible understanding of the term “scenography” being neither new-fangled, pretentious, anti-textual nor all three. The reader, I hope, is convinced of its viability.

© Polyglot Press and Promotions, 2012.

^ back to top of the page

References

- The American Society of Cinematographers Website. 2012.

- Associated Designers of Canada’s Website.

2010.

- International Cinematographers Guild, Local 667 Website.

2008.

- Jaynes, Julian.

The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind.

University of Toronto Press, 1982.

- Payne, Darwin Reid.

The Scenographic Imagination.

Southern Illinois University Press, 1981

- Saito, Noriko.

E-mail interviews with the Japan Foundation Program Officer, Toronto.

December 24, 2012—January 9, 2013.

^ back to top of the page

To Cite this Page

| CMS |

“A Practical Definition of Scenography.” Valérie C. Kaelin Website; Scenography; Theory; December 24, 2012. Accessed Month, Day,Year. http://www.valerieckaelin.com

|

| MLA |

Kaelin, Valérie C., “A Practical Definition of Scenography.”Toronto, 13 Dec. 2012. Web. Add Day, Abbreviation for Month, Year. |

|